Have you ever thought about what it was like for the first American colonists? Can you imagine the thrill of seeing what would become your new homeland after traveling across the vast ocean that separates the United States from Europe?

Have you ever thought about what it was like for the first American colonists? Can you imagine the thrill of seeing what would become your new homeland after traveling across the vast ocean that separates the United States from Europe?

While it may be easy to imagine the excitement that the colonists had when they saw the shoreline, it’s not nearly as easy to envision what those brave pioneers actually saw as their ships approached this continent. That’s because the landscape of this country has changed dramatically in the centuries that have passed since the arrival of the first colonists.

When European settlers began to arrive in the United States hundreds of years ago, the country was largely covered by forests. These virgin forests included what are now considered “old-growth forests.” Also referred to as a “primary forest,” a “primeval forest,” and a “late seral forest,” an old-growth forest is a forest that has reached a significant age without being disturbed by humans or a destructive natural occurrence such as a wildfire. Because it’s been undisturbed for hundreds or thousands of years, an old-growth forest typically has biodiversity that can’t be found elsewhere. In fact, old-growth forests are the home of many endangered species of both plants and animals, including the northern spotted owl and the marbled murrelet.

In addition to being the home of rare plants and wildlife, old-growth forests have certain characteristics that make them different from younger forests. While you may think that every tree in an old-growth forest is ancient, a primeval forest ordinarily includes trees of varying ages, which makes it possible for the forest to regenerate over time and maintain a stable ecosystem. Old-growth forests often have large, healthy trees next to standing dead ones. An old-growth forest usually has a multi-layered canopy, dotted with gaps that are the result of the death of individual trees. You can normally find raw, woody debris on the ground beneath a primary forest.

Although old-growth forests were abundant when the first settlers arrived in the United States, we have depleted them as our population has grown and spread throughout the country. According to the University of Michigan, people have cleared away approximately 90 percent of the primeval forests that originally blanketed America’s lower 48 states. While estimates vary, Global Forest Watch reports that old-growth forests provide only seven percent of America’s total forest cover.

Although old-growth forests were abundant when the first settlers arrived in the United States, we have depleted them as our population has grown and spread throughout the country. According to the University of Michigan, people have cleared away approximately 90 percent of the primeval forests that originally blanketed America’s lower 48 states. While estimates vary, Global Forest Watch reports that old-growth forests provide only seven percent of America’s total forest cover.

The American Chestnut

Once considered the “Queen of the Eastern American Forest,” the American chestnut used to dominate old-growth forests from southern Maine across the Midwest to Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, down south to Alabama and Mississippi and eastward into the Appalachians. Found throughout the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Cumberland Plateau, the American chestnut once populated more than 159,165 acres, or 31 percent, of what is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

First cultivated in 1800, the American chestnut grew to a height of 100 feet and a diameter of up to 26 feet. The tree had large, wide-spreading branches and a characteristic broad, rounded crown. The American chestnut typically grew on mountains, hills and slopes in well-drained, rocky soil. The American chestnut produced creamy, yellowish blooms in June and July, which gave off a powerful yet pleasant aroma. These blooms gave way to nuts, which typically fell after the first frost in the fall months.

Before the American chestnut’s population was decimated by a catastrophic blight beginning in the early 1900s, the tree competed well with other forest trees and often grew alongside oak, hickory, maple and birch trees. As a living tree, the American chestnut was resistant to bugs and it reproduced through seedlings and sprouts.

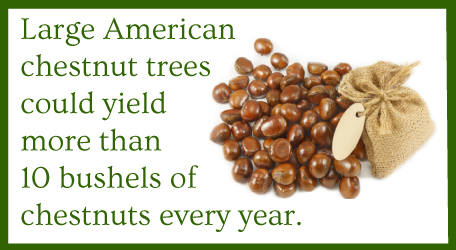

Large American chestnut trees could yield more than 10 bushels of chestnuts every year. In certain parts of the Appalachians, chestnuts would cover the forest floor four inches deep every fall. Chestnuts were a major food source for various game animals, including squirrels, turkeys, deer, grouse, raccoons and black bears. Certain insects also relied on chestnuts as a primary food source. A former representative of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Paul Opler estimates that at least seven moths native to the southern Appalachians became extinct after the chestnut blight cut off their food supply.

Like many animals and insects, humans also relied on chestnuts as a food source. Native Americans often added chestnuts to dough made from cornmeal. Settlers seasonally baked chestnuts for their own consumption. They also traded or sold chestnuts for profit in urban areas. In the Smoky Mountains, the money people made from the sale of chestnuts was referred to as “shoe money,” because area residents often used these funds to buy footwear for their children before the winter arrived. Domestic pigs also fed on chestnuts, which gave the animals’ meat a nutty flavor.

Native Americans used the leaves of the American chestnut for medicinal purposes as well. Leaves from the tree allegedly relieved heart problems. The tree’s sprouts were sometimes made into a tea, which was then used to treat open sores and to heal wounds.

Native Americans used the leaves of the American chestnut for medicinal purposes as well. Leaves from the tree allegedly relieved heart problems. The tree’s sprouts were sometimes made into a tea, which was then used to treat open sores and to heal wounds.

The reddish-brown wood harvested from the American chestnut was lightweight, soft and easy to work with. It also resisted decay, warping and shrinking. Given the lumber’s resistance to decay and its other noteworthy characteristics, the straight-grained wood featured in many constructions, including the following:

- Cabins

- Barns

- Caskets

- Posts

- Poles

- Pilings

- Railroad Ties

- Split-Rail Fences

- Ship Masts

- Furniture

- Roofing Shingles

- Telephone Poles

- Siding

Although the American chestnut was known for the fruit it bore and the quality of the wood the tree yielded, it also became known as a source of tannic acid, a substance used to tan leather. In Tennessee, workers cut 50,000 cords of wood every year to supply tannic acid to commercial tanneries operating before 1912. By 1930, at least 21 plants fueled by the American chestnut operated in the southern Appalachians. Combined, these plants produced more than 50 percent of the country’s supply of vegetable-based tannins.

The Chestnut Blight

By the start of the twentieth century, many residents along the east coast of the United States had come to rely on the American chestnut as a source of food, shelter and much needed income. Unfortunately, a blight commonly referred to as the “Chestnut blight” was introduced in the United States in the early 1900s, which would make it impossible for people to continue to rely on the American chestnut for their basic needs.

The scientific name for the Chestnut blight is “Endothia parasitica.” Herman W. Merkel, a forester at the Bronx Zoo, was the first to notice the blight on the American chestnut trees at the New York Zoological Garden. It is widely speculated that the blight was accidentally brought into America when Asian chestnut trees were imported to stock plant nurseries. Merkel partnered with W.A. Murrill, a mycologist who worked at the New York Botanical Garden, to identify and name the disease.

The Chestnut blight is a fungus that has two kinds of spores: large, dry discs, and a smaller, sticky spore. The larger spore spreads by the wind while the smaller one does so by rain. Birds and tools (such as axes used on an afflicted tree) could also transmit the spores.

These deadly spores enter American chestnut trees through cracks and wounds on the trees’ bark. Once in a tree, the fungus spreads to the inner parts, girdling it. The leaves above the point where the spores entered a tree die as a result. The tree’s limbs then die in succession. A tree infected with the Chestnut blight will develop orange-colored cankers on its limbs and trunk until they entirely encircle the stem.

When you see a canker on an American chestnut tree, the part of the tree that has the blemish is dead and is impossible to revive. Cankers prevent the parts of the tree that are above them from getting vital nutrients, which causes them to die in as little as four days. When a canker encircles the trunk of an American chestnut, it destroys the tree’s cambium layer entirely.

The American chestnut responds to this “death grip” by sending out shoots from below the canker, something it’s able to do because the part of the tree that is under the canker, including its roots, remain unaffected by the blight. Although it may seem that the tree’s ability to reproduce even when it’s under attack by the Chestnut blight would ensure its survival in the forest, the new trees typically only reach a height of 10 to 12 feet before they become infected by the blight as well. Because of this, the introduction and spread of the Chestnut blight effectively brought upon the extinction of the American chestnut for commercial purposes.

After its discovery on the premises in 1904, it didn’t take long for the Chestnut blight to kill the American chestnut trees that lined the landscape at the Bronx Zoo. It also didn’t take much for the disease to spread and infiltrate other areas of the country where the American chestnut formerly thrived.

In 1907 and 1908, American chestnut trees at the New York Botanical Garden started displaying the telltale signs of the malady, which include wilting leaves, rupturing bark and the disease’s unmistakable cankers. The disease spread as much as 50 miles per year, reportedly spotted in New Jersey, Virginia and Maryland as early as 1906. The chestnut blight also traveled northward, devastating forests in Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Realizing that the demise of the American chestnut also threatened the various industries that were dependent on the tree’s continued existence, the federal government appropriated funds to fight the disease in 1911-1913. Studies in Pennsylvania showed that tree surgery, chemical sprays or fungicide injections couldn’t prevent the spread of the disease. In North Carolina’s southern Appalachians, efforts to stop the spread of the blight included cutting an isolation strip across the mountain range. When it became obvious that the disease had already reached Georgia, foresters abandoned the notion that a quarantine line would successfully prevent the spread of the chestnut blight.

When World War I drew the United States into battle, the federal government cut funding for the study and prevention of chestnut blight. By the mid-1920s, the disease was present in the southern Appalachian Mountains, the site most of the tannin extract industry called home. While it was still possible to harvest American chestnut trees for years after the blight hit, because of their inherent heartiness, many people suffered the economic impact of the chestnut blight much faster.

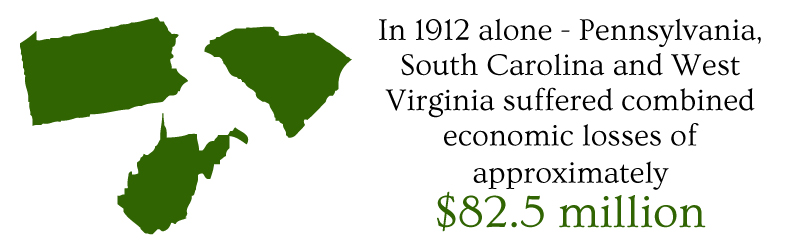

In 1912 alone, it is estimated that the states of Pennsylvania, South Carolina and West Virginia suffered combined economic losses of approximately $82.5 million as a result of the chestnut blight. By 1950, even the American chestnut trees in southern Illinois were destroyed by Endothia parasitica. Between 1910 and 1950, it is suspected that the chestnut blight killed 3.5 billion trees over 3.6 million hectares of land.

For about a decade after the blight struck the southern Appalachians, residents were still able to collect nuts from the remaining healthy American chestnut trees. By 1940, the production of chestnuts was limited to the sprouts and seedlings that somehow still managed to survive.

Shortly after the Chestnut blight was discovered, Frank Meyer, a plant explorer for the United States Department of Agriculture, determined that the fungus was present in Japan and China. Since horticulturalists located in the U.S. were able to import Asian chestnut nursery stock beginning in 1876, it was widely speculated that the disease was unintentionally and unknowingly brought into the country by one of these shipments. Meyer’s determination and this suspicion led to the passage of the Plant Quarantine Act in 1912, which was designed to prevent a disaster like the one that destroyed the American chestnut, as it was known at that time.

Wormy Chestnut

A byproduct of the Chestnut blight, wormy chestnut helped to soften the blow the fungus delivered to the economy. “Wormy chestnut” refers to American chestnut lumber harvested from trees killed by the blight. Since some trees were left standing for years after the blight killed them, insects subsequently damaged them. The insects bored holes in the trees and discolored them, giving the lumber that was derived from these trees a unique, eye-catching appearance.

The beetles responsible for creating wormy American chestnut lumber quickly mass-produced due to the nutrition they found in the deceased American chestnut trees that remained standing in the Appalachian Mountains. This mass reproduction caused the beetles to infect other kinds of trees in the mountain range, including oak trees, pine trees and black walnut trees.

Sober Paragon Chestnut Farm

While wormy chestnut helped stave off the financial effects of the chestnut blight for some in the short-term, the blight decimated the financial well-being of others almost immediately after it struck. The Sober brothers suffered the negative effects of the chestnut blight within years of the fungus destroying the farm the four men had purchased from their father in 1896.

While wormy chestnut helped stave off the financial effects of the chestnut blight for some in the short-term, the blight decimated the financial well-being of others almost immediately after it struck. The Sober brothers suffered the negative effects of the chestnut blight within years of the fungus destroying the farm the four men had purchased from their father in 1896.

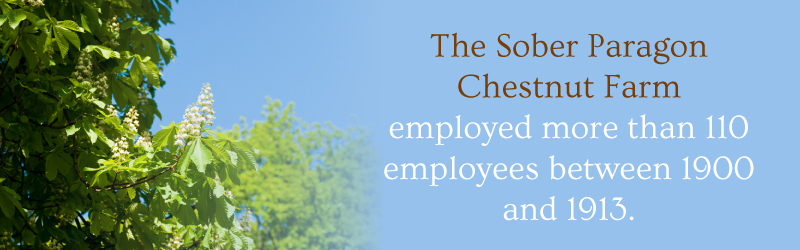

Located in Northumberland County about seven miles from Shamokin, PA, the Sober Paragon Chestnut Farm spanned hundreds of acres. The Irish Valley farm was thought to be the largest chestnut tree farm operating in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. Located on land that was owned by members of the Sober family dating back to the late 1700s, the farm employed more than 110 employees at the height of its operations between 1900 and 1913. From its humble beginnings, the brothers grew their farm into what became the largest commercial farm of its kind in the world.

In addition to being a property full of American chestnut trees, the family farm was home to a half-mile racetrack. While the Sober brothers were successful businessmen, they were also well-known sharpshooters who were purportedly more accurate than Bill Hickok, a Wild West legend the brothers are rumored to have competed against.

Given their success with grafting and other farming techniques, the Sober brothers were recognized as experts in their field and agricultural professors consulted them regularly. The brothers shipped their American chestnut tree saplings to cities throughout the country, but eventually received notice that some of their saplings were afflicted with a disease.

Realizing their farm had been infiltrated by the chestnut blight, the Sober brothers took immediate action to try to save their livelihood. They traveled. They consulted. And they performed experiments they hoped would make their trees resistant to the blight. Unfortunately, their efforts were fruitless.

The brothers were unable to stop the devastating effects of the chestnut blight and were forced to mortgage their once-thriving farm to cover their expenses. The family-owned and operated farm sold in 1920.

Breeding a Blight-Resistant American Chestnut

After the Chestnut blight destroyed the American chestnut population throughout the United States, numerous scientists and publicly and privately funded groups began to devise ways to breed a new chestnut tree that was resistant to the deadly fungus. Efforts were made to breed the American chestnut with Asian chestnut trees. While the Asian trees could also be infected with the Chestnut blight, the fungus only causes the Asian trees to suffer cosmetic damage instead of killing them.

The United States Department of Agriculture funded a comprehensive breeding program that crossed American chestnut trees with their Asian counterparts. The goal was to create a tree that had all of the positive attributes famous in American chestnut trees as well as the resistance to Chestnut blight that the Asian trees had. Because of the genetics that control the Asian trees’ resistance and the differences that exist between the different types of trees involved, the program only saw limited success.

The United States Department of Agriculture suspended its efforts to create a blight-resistant American chestnut tree in 1960. At that time, the Connecticut Program, which was started by plant breeder, Dr. Arthur Graves, in 1930 on his own land, was pushed to the forefront of the research on crossbreeding chestnut trees. The Connecticut Program remains the longest continuously running chestnut tree breeding program in the United States to this day.

When interest in reviving the American chestnut renewed in the early 1980s, the state of Virginia founded American Chestnut Foundation. Like the Connecticut Program, the non-profit is committed to producing a blight-resistant American chestnut tree that future generations can enjoy for rest and recreation and use for business purposes.

The current approach to breeding a blight-resistant American chestnut involves the backcross method. This method starts by crossing an Asian parent tree with an American parent to produce trees that are half-Asian and half-American. The offspring of this pairing grow for several years and are tested for their resistance to the chestnut blight. Once the trees with the strongest resistance are identified, they are backcrossed with the American parent tree.

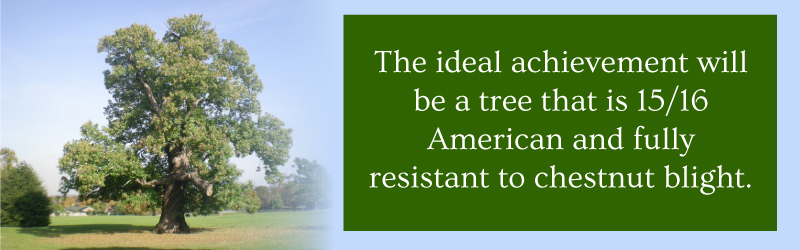

Surviving trees are backcrossed several additional times with the goal of further increasing their resistance to blight and the amount of their makeup that is attributable to the American chestnut. After six crosses, the ideal achievement will be a tree that is 15/16 American and fully resistant to chestnut blight.

Backcrossed trees need six years to mature and produce nuts to plant. Trees that are intercrossed instead only need five years until they’re ready to be planted. Since this breeding method involves a total of six crosses, it means that it will take at least 33 years to produce a tree that is predominantly American and resistant to chestnut blight.

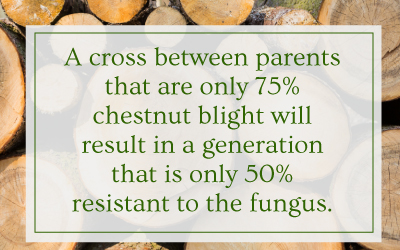

While the backcross method is promising, maintaining a sufficient diversity among the trees it produces is a primary concern that could jeopardize its ultimate, lasting success. A cross between parents that are only 75 percent resistant to chestnut blight will result in a successive generation of trees that is only 50 percent resistant to the fungus. A cross between parents that are fully resistant to the blight will produce trees that are also completely immune. To maintain the diversity required for the backcross breeding method to be successful, breeders use trees from multiple locations with varying levels of diversity.

While the backcross method is promising, maintaining a sufficient diversity among the trees it produces is a primary concern that could jeopardize its ultimate, lasting success. A cross between parents that are only 75 percent resistant to chestnut blight will result in a successive generation of trees that is only 50 percent resistant to the fungus. A cross between parents that are fully resistant to the blight will produce trees that are also completely immune. To maintain the diversity required for the backcross breeding method to be successful, breeders use trees from multiple locations with varying levels of diversity.

Reclaimed American Chestnut Lumber

The market for original American chestnut lumber disappeared in the years and decades following the Chestnut blight due to a lack of supply. The backcross breeding method may ultimately be successful at producing a crop of American chestnut trees that are virtually indistinguishable from their predecessors. This comes with the exception of their newfound resistance to blight, however, it may take several generations before the method yields meaningful results, if any at all.

While this is true, you can still enjoy antique wormy chestnut flooring in your home or place of business. It’s possible to get wormy chestnut wide plank flooring reclaimed from structures that have simply outlived their practical usefulness.

Generations of early Americans used chestnut lumber to build the structures they needed to survive and thrive. With farming being the backbone of the United States in the country’s formative years, the construction of barns often took precedence over the building of homes. Because American chestnut trees were normally big and yielded strong, straight lumber that didn’t warp or shrink, they were typically used to create the structural components of barns in the areas where these trees grew. This means that American chestnut was often used to make things like beams, while a softer wood such as pine may have been used to make joists in the same structure.

Being so resistant to insects and rot, craftsman used the American chestnut to create many other things, including fences, some of which still dot the American landscape today. Since many of the American chestnut trees that remained standing after the chestnut blight struck became infested with beetles, much of the chestnut lumber that is being reclaimed is wormy chestnut. This means that you can typically see the boreholes created by the beetles that were feeding off of the dead trees before they were harvested.

The bore holes give reclaimed wormy chestnut flooring a distinctive look and feel that are only enhanced by the saw marks, nail holes and cracks that the wood experienced when it was originally used decades ago. Of course, the American chestnut tree’s enduring natural beauty completes the look that you can only get from antique wormy chestnut flooring.

In addition to giving your living or work space a look and feel that are truly unique, installing reclaimed wormy chestnut flooring instead of newly manufactured flooring helps to protect the environment. By repurposing reclaimed materials, you are keeping them out of the nation’s landfills. Just as importantly, you’re also preserving an irreplaceable part of the nation’s past.

Superior Hardwoods of Montana

At Superior Hardwoods of Montana, our mission is for you to Let Us Guide You Through The Woods®. We enhance your building experience by creating lasting relationships based on knowledge, diligence and consideration. Founded in 1977, our family-owned and operated business has helped people throughout the nation find the materials they need to complete their building projects with the design characteristics they can’t find in other products.

In 1990, our founder, John Medlinger, developed an interest in antique and reclaimed building materials, often overlooked or discarded unnecessarily. Thanks to Medlinger’s vision, these vintage materials are now available for you to incorporate into the design of your home.

We are proud that we have the largest selection of in stock flooring options available in the western United States, with over 100,000 square feet of flooring onsite. We have over 11 acres of reclaimed architectural lumber that can add a literal piece of American history to your home. As a leader in the reclaimed and antique building materials industry, we appreciate the historical value of our products and we look forward to seeing them preserved as part of today’s building projects.

Recently, we introduced the Wilderness and Heirloom Series as part of our Pioneer Series of flooring options. If you’re interested in experiencing a piece of history that dates back to the time when stagecoaches and horses were the primary modes of transportation and cowboys ruled the land, we invite you to view our exciting new Wilderness and Heirloom Series.

The Heirloom Series features a combination of both soft and hard woods, including American chestnut. We created this series by exclusively using wood between 100 and 150 years old. This means no new material or pallet material was used to make this breathtaking series of flooring options.

The wood used in our Heirloom Series has stood the test of time, and our wide plank flooring alternatives will continue to stand with you and your family for generations to come. Some people choose our reclaimed wormy chestnut flooring because it’s environmentally friendly and provides a connection to the country’s rich past. Others prefer our wormy chestnut wide plank flooring because it enables them to create a completely customized look that satisfies their personal decorating preferences.

At Superior Hardwood of Montana, we can handcraft every plank that you’ll use in your home to ensure it provides the exact look and feel you want your living space to have. Whether you want smooth or original saw marks, stained or natural wood or slats in just one or multiple widths, we’ll create a custom floor plan that meets your exacting standards in our 4,000 square foot mill.

Our knowledge and unwavering dedication to providing the best customer service possible are what set us apart from our competitors. We treat our clients as if they were our friends and family members because that’s genuinely what we consider them to be. Our mission is to establish long-lasting relationships with our clients that will enable them to celebrate their homes with antique wormy chestnut flooring that they and their children and grandchildren will enjoy for years to come.

Most of our representatives have been with us for at least six years. This means our staff members have the knowledge and experience to provide thoughtful, meaningful advice at every stage of a given project. You can feel confident when you Let Us Guide You Through The Woods® because you’ll know you’re getting advice that is reliable, truthful and backed by years of experience.

Whether you are a homeowner or you’re part of a design or architectural firm that helps owners with their building projects, we can help you find the reclaimed flooring you need to make your project truly your own. Our experts have assisted many others throughout the decades and we’ll be happy to help you create a custom look that reflects your personality as well as it gives your home the historical look and feel you want your living space to have.

We’ve helped people just like you achieve their design dreams and we’re flattered that so many of them have shared their thoughts about their experiences with our company. Here are some of the comments our valued clients have shared with us:

“I would like to express my support for John at Superior Hardwoods and Millwork. As an architect for over 20 years that relies on the quality and the unique resource of recycled wood, I have found Superior Hardwoods to be an exceptional vendor. Recycled wood requires an expertise in handling and distribution. Superior Hardwoods has consistently provided us the resources to complete many high-end custom homes.” — Pearson Design Group

“Miller Architects has relied on Superior Hardwoods of Montana to provide reclaimed wood for our projects over the past twenty years. Their product and service has been outstanding in every way, making our projects enjoyable to produce and successful beyond compare. They are a top rate company to work with.” — Candace Tillotson-Miller, Miller Architects

“I would highly recommend Superior Hardwoods of Montana to anyone who wants a quality product, and knowledgeable employees providing great customer service.” — Anonymous Client

“First, I want to thank you for the incredible service I have Always received at Superior Hardwoods of Montana… Thank you again for such great help!” — Scott Holmes

“All the staff at Superior Hardwood were extremely helpful and very knowledgeable. They helped us from selecting the wood, gave me instructions on how to do the installation as well as doing the sanding and finishing.” — Anonymous Client

“Superior [Hardwoods of Montana] always supplies top quality material and backs it up with great response and service. Shipping is always a breeze.” — Bill Strange

If you’re thinking about incorporating wormy chestnut wide plank flooring into the design of your next building project, we encourage you to contact Superior Hardwoods of Montana. Like we did for the clients quoted above, we’ll help you find the flooring that will provide the look and feel you’re looking for. We’ll customize your floor so that it truly represents you and is your very own, unique piece of American history.

When you’re ready to Let Us Guide You Through The Woods®, give us a call. Based on your personal preferences, we’ll prepare a custom quote for the reclaimed wormy chestnut flooring option of your choice. We look forward to helping you make your design dreams come true. Contact Superior Hardwoods of Montana to learn more today.